Eleanor set her shoulders. She could do this, she was good at learning, very good, much better than some smug village girl who was only here to try and beat her, if Eleanor left, Maggie would probably lose two helpers, not just one.

Maggie’s eyes looked through her again, but all she said was. “And you needn’t think of getting out of things with a story this time. The children are all with Samuel this afternoon, learning their letters.”

Martha spoke. “For all the use that is. The hours I spent cooped up in that stuffy little room, copying out stupid words for no reason. I don’t need to read, nor write, and don’t appreciate people wasting my time.”

Maggie looked at Eleanor who replied as she took up her carding combs. “Each to their own. I like knowing the contents of a trade deal before it’s made, not after I’ve been delivered goods I didn’t agree to.”

Martha snorted. “If you have to rely on writing for trades, then you’re dealing with the wrong people. The only person worth transacting with is one who’s word you trust, and who shows you the goods before you agree.”

“And if the goods are in a different city? Or the person speaks a different language?”

Martha looked scornful. “Why would I deal in trades like that? I’ll take what I can see in front of me, from people I know.”

Eleanor shrugged and focused on the wool. Martha watched her for a while, then said. “And what use is your fancy reading and language speaking now? You ain’t going to be dealing in far-away trades from here.”

It was horrible to realise the other girl was right, Eleanor affected nonchalance. “So I’ll use it for things closer to home, such as making sure that swindler at the farm we stayed at gives equal and fair return for the wood he gets. You need something in writing to get in front of the town magistrate.”

Martha looked set to retort, but Maggie intervened. “Less chattering, more carding. I want at least a skein of decent quality yarn from each of you by the time the shadows start creeping out.”

When Maggie released them, several hours later, she had a small skein of lumpy, uncertain yarn from Eleanor and something more closely resembling acceptable from Martha, although the older woman still grumbled over it.

Cadan was outside, waiting, when she left Maggie’s cottage in Martha’s wake.

The other girl sneered. “Are you pleased with the useless piece of town trash you threw me over for then? She can’t wash, spin, weave, or do anything.”

Her husband looked at Martha thoughtfully, then said. “Nora is more valuable to me than gold.”

He walked forward to take Eleanor’s hand as Martha hissed. “I’m better.”

Cadan replied. “Maybe for that castle messenger; is it Tim, or Tom? Not for me.”

He turned his back on Martha and said. “You’ve not even been given a proper tour of the village yet, have you.”

Eleanor shook her head. “Just here, the bath house and the central clearing. But I would like to talk to Samuel too.”

Martha was still there and apparently determined to be acknowledged. “What’s the point? You’re just going to be delivering her back to town as soon as the weather closes in.”

Cadan ignored her, supposedly. “It’s a few months before we can think to make a start on our own place, but now’s a good time to get a feel for where we might want to clear and build.”

That earned him her best smile. “That’s a wonderful idea.”

Martha stomped off and Cadan began his tour. “You know Crafter’s Clearing here, there’s a good flat area on the western side for a decent-sized place, once cleared, and if you apprentice to Maggie, would put you in easy reach of the workroom.”

Eleanor tugged him towards the path back to the main area. “I’m not sure I’d want to be directly under Maggie’s nose the whole time. And I don’t think the Smiths would make happy neighbours, so that’s River Clearing out. Where else could we go?”

They explored Woodcutter’s Clearing, which was broad and bright but had little room for expansion. The land surrounding it was peppered with rocky outcrops and the woodcutting families were polite but not welcoming as they walked past the houses.

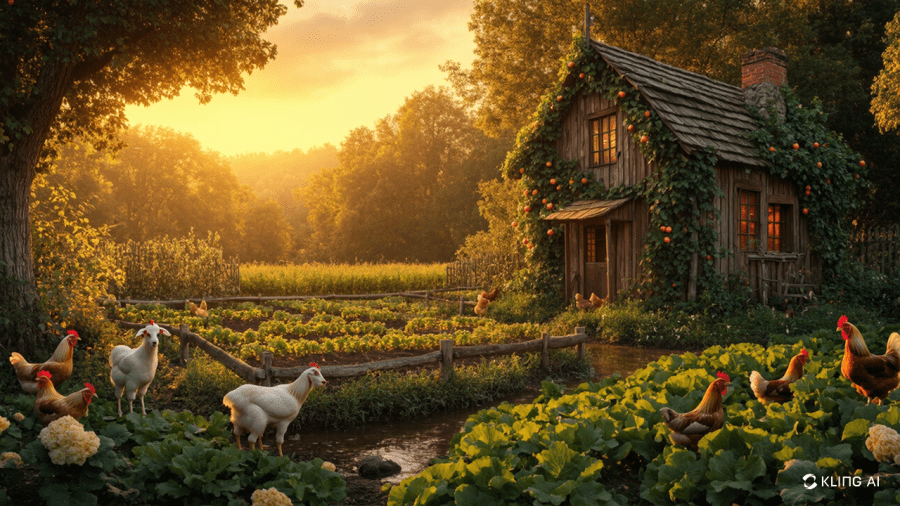

Garden Clearing was the largest, bordering a fresh stream and full of densely planted beds of vegetables, well-fenced chickens and goats, and even a small orchard. Cadan frowned as he looked around it. “It’s another one that’s hard to expand, and I don’t think they’d like us taking the place of the fruit trees.”

He led her back to the central area and they looked around it appraisingly. Eleanor said. “It feels like they need to start another cluster, but you need more than one cottage built to do that, more than one family to move, or it’ll be strange.”

Cadan’s hum of agreement was absent-minded at best, and he changed the subject. “So now we’ve looked around, shall we see if Samuel has a minute or two to spare?”